In May 2024, The National Council of Urban Indian Health (NCUIH) submitted written testimony to the House and Senate Appropriations Subcommittees on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (LHHS), as well as to the House and Senate Appropriations Subcommittees on Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies regarding Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 funding. NCUIH advocated in its testimony for full funding for the Indian Health Service (IHS) and Urban Indian Health and increased resources for key health programs.

In the testimonies, NCUIH requested the following:

- Full funding at $53.85 billion for the Indian Health Service (IHS) and $965.3 million for Urban Indian Health for Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 (as requested by the Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup).

- Maintain Advance Appropriations for the Indian Health Service, until mandatory funding is authorized and protect IHS from sequestration.

- Fund the Initiative for Improving Native American Cancer Outcomes at $10 million for FY25.

- Fund the Good Health and Wellness in Indian Country (GHWIC) Program at $30 Million for FY25.

- Protect Funding for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment.

- Reclassify Contract Support Costs and 105 (l) Tribal Lease Payments as Mandatory Appropriations.

Next Steps:

These testimonies will be considered by the House and Senate Appropriations Committee and used in the development of FY25 spending bills. NCUIH will continue to advocate for these requests in FY 2025 and work closely with Appropriators throughout the remainder of the Appropriations process.

Full Text:

My name is Francys Crevier, I am Algonquin and the Chief Executive Officer of the National Council of Urban Indian Health (NCUIH), a national representative of the 41 UIOs contracting with the Indian Health Service under the Indian Health Care Improvement Act (IHCIA) and the American Indians and Alaska Native patients they serve. On behalf of NCUIH and the UIOs we serve, I would like to thank Chair Baldwin, Ranking Member Moore Capito, and Members of the Subcommittee for your leadership to improve health outcomes for urban Indians.

We respectfully request the following:

- $53.85 billion for the Indian Health Service (IHS) and $965.3 million for Urban Indian Health for Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 (as requested by the Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup).

- Maintain Advance Appropriations for the Indian Health Service, until mandatory funding is authorized and protect IHS from sequestration.

- Fund the Initiative for Improving Native American Cancer Outcomes at $10 million for FY25.

- Fund the Good Health and Wellness in Indian Country (GHWIC) Program at $30 Million for FY25.

- Protect Funding for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment.

NCUIH Supports Tribal Sovereignty

First, I would like to emphasize that NCUIH respects and supports Tribal sovereignty and the unique government-to-government relationship between our Tribal Nations and the United States. NCUIH works to support those federal laws, policies, and procedures that respect and uplift Tribal sovereignty and the government-to-government relationship. NCUIH does not support any federal law, policy, or procedure that infringes upon, or in any way diminishes, Tribal sovereignty or the government-to-government relationship.

Urban Indian Organizations Play a Critical Role in Providing Health Care for American Indian and Alaska Native People

UIOs were created by urban American Indian and Alaska Native people, with the support of Tribal leaders, starting in the 1950s in response to severe problems with health, education, employment, and housing caused by the federal government’s forced relocation policies[1]. Congress formally incorporated UIOs into the Indian Health System in 1976 with the passage of IHCIA. Today, over 70% of American Indian and Alaska Native people live in urban areas. UIOs are an integral part of the Indian health system, comprised of the Indian Health Service, Tribes, and UIOs (collectively I/T/U), and provide essential healthcare services, including primary care, behavioral health, and social and community services, to patients from over 500 Tribes[2] in 38 urban areas across the United States. There are four different UIO facility types, including full ambulatory, limited ambulatory, outreach and referral, and outpatient and residential alcohol and substance abuse treatment, that offer a wide range of healthcare services.

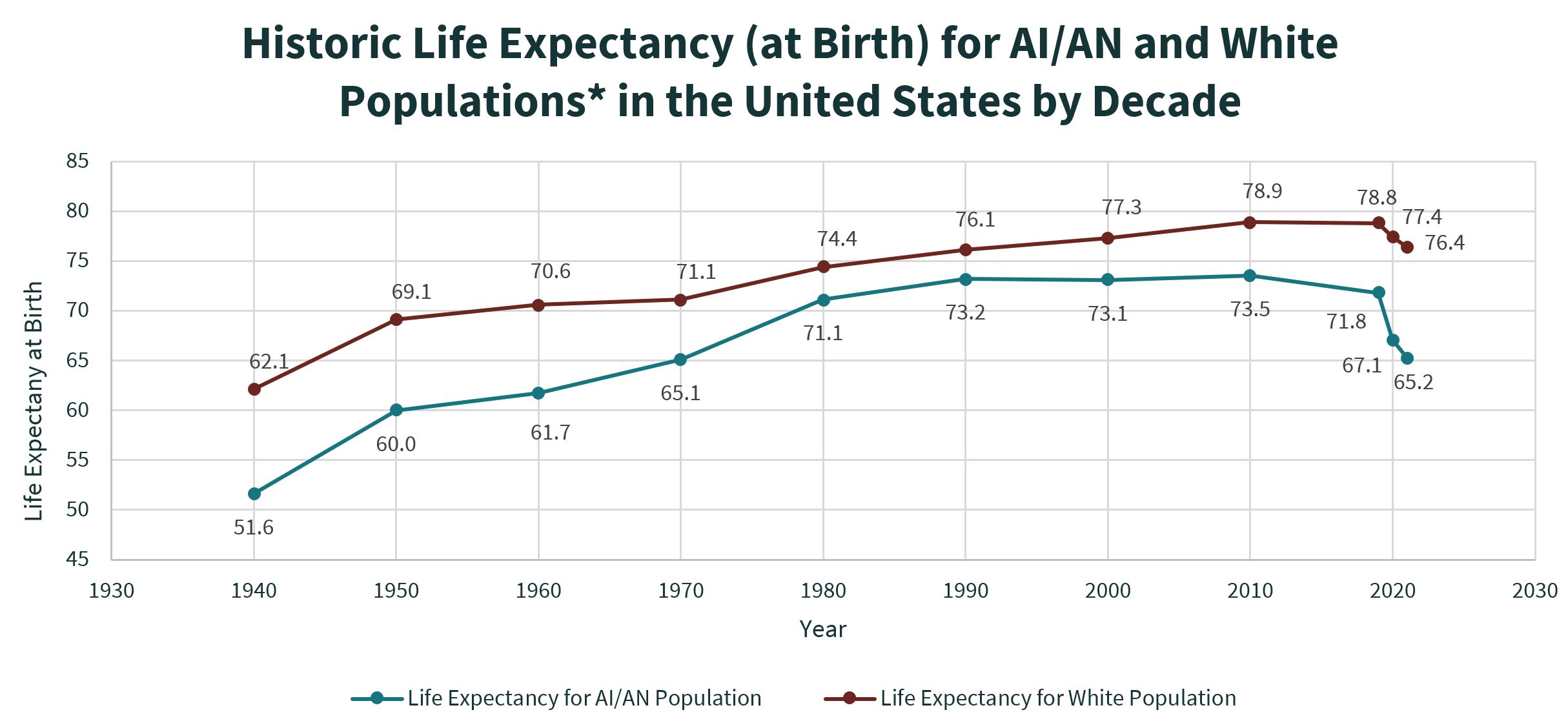

UIOs are on the front lines in providing for the health and well-being of American Indian and Alaska Native people living in urban areas, many of whom lack access to care that would otherwise be provided through IHS and Tribal facilities. American Indians and Alaska Native people experience major health disparities compared to the general U.S. populations, including, lower life expectancy,[3] and higher rates of infant and maternal mortality. A lack of sufficient federal funding plays a significant role in these continuing devastating health disparities,[4] and Congress must do more to fully fund the Indian health system to improve health outcomes for all American Indian and Alaska Native people.

Request: Fully fund the Indian Health Service at $53.85 billion and Urban Indian Health at $965.3 million for FY25

The United States has a trust responsibility to provide “federal health services to maintain and improve the health” of American Indian and Alaska Native people. This responsibility is codified in IHCIA.[5] Additionally, it is the policy of the United States “to ensure the highest possible health status for Indians and urban Indians and to provide all resources necessary to effect that policy.”[6] To finally fulfill its trust responsibility, we request that Congress fully fund Indian Health at $53.85 billion for the Indian Health Service and $965.3 million for Urban Indian Health. These amounts reflect the recommendations made by the Tribal Budget Formulation Work Group (TBFWG), a workgroup comprised of Tribal leaders representing all twelve IHS service areas and serving all 574 federally recognized Tribes.

According to the TBFWG, fulfillment of the trust responsibility “remain[s] illusory due to chronically underfunded and woefully inadequate annual spending by Congress.”[7] Congress must prioritize increasing funding, as the current FY24 allocation of $6.96 billion for IHS and $90.49 million for Urban Indian Health represents only 12.9% and 9.4% respectively of the total FY24 funding requested by Tribes and UIOs to adequately address current needs.

UIOs are primarily funded through a single line item in the IHS budget, the Urban Indian Health line item, and without a significant increase to this line item, UIOs will continue to be forced to operate on limited and inflexible budgets, that limit their ability to fully address the needs of their patients. As one UIO leader highlighted, “funding to the Urban Indian Health line item is critical in ensuring that our funding better meets the needs of urban tribal citizens who come to us seeking medical, dental, and behavioral health care. Increased funding means that we can worry less about having to deny or delay care because of budget constraints.” For example, current funding levels pose challenges for UIOs in offering competitive salaries to hire and retain qualified staff who are essential for UIOs to continue to deliver quality care to their patients. Additionally, UIOs need resources to expand their services and programs to address the needs of their communities, including addressing pressing issues such as food insecurity, behavioral health challenges, and rising facilities costs. One UIO reported, “increased funding will allow our UIO to sustain our program capacity, maintain our workforce, address infrastructure needs, and expand health services that are greatly needed within our community.” Increased investments in Urban Indian Health will continue to result in the expansion of health care services, increased jobs, and improvement of the overall health in urban Native communities.

Request: Retain Advance Appropriations for IHS until Mandatory Funding is Authorized and Protect IHS from Sequestration

Advanced appropriations allowed the I/T/U system to operate normally and without fear of funding lapses during the entire FY24 budget negotiation process. Among other benefits, when IHS distributes their funding on time, our UIOs can pay their doctors and providers without disruption, ensuring continuity of care for UIO patients. Additionally, advanced appropriations allow our UIOs to ensure they can stay open and provide patients with critically needed care, even in the event of a government shut down. We emphasize that advanced appropriations are a crucial step towards ensuring long-term, stable funding for the I/T/U system and, therefore, it is imperative that you include advance appropriations for IHS FY26 in the final FY25 Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act.

While advance appropriations are a step in the right direction to avoid disruptions during government shutdowns and continuing resolutions, mandatory funding is the only way to assure fairness in funding and fulfillment of the trust responsibility. As the President’s FY25 budget notes, “Mandatory funding is the most appropriate, long-term solution for adequate, stable, and predictable funding for the Indian health system.”[8] We request your support for mandatory funding, and until authorizers act to move IHS to mandatory funding, we request you continue to provide advance appropriations to the Indian health system to improve certainty and stability.

We also request that this Committee protect IHS from sequestration through an amendment to Section 255 of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act[9]. Sequestration forces Indian Health Care Providers to make difficult decisions about the scope of healthcare services they can offer to American Indian and Alaska Native patients. For example, the sequestration of $220 million in IHS’ budget authority for FY13 resulted in an estimated reduction of 3,000 inpatient admissions and 804,000 outpatient visits for American Indian and Alaska Native patients[10].

Sequestering funds reduces UIOs’ ability to provide essential services to their patients and communities, delaying care and reducing UIO capacity to take on additional patients. One UIO leader emphasized that loss of funding “translates into Tribal citizens lacking access to care that is guaranteed to them through the trust and treaty obligations held by the United States. Cuts mean UIOs can’t provide things like insulin for diabetics, counseling services for survivors of domestic violence, and oral surgery for our relatives.”

Request: Fund the Initiative for Improving Native American Cancer Outcomes at $10 million for FY25

The FY24 LHHS spending bill appropriated $6 million in new funding to address Native American cancer outcomes, by creating the Initiative for Improving Native American Cancer Outcomes.[11] The Initiative will support efforts including research, education, outreach, and clinical access to improve the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of cancers among American Indian and Alaska Native people. The purpose of the Initiative is to ultimately improve the screenings, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer for American Indian and Alaska Native patients.

This Initiative will be critical to addressing cancer-related health disparities in Indian Country. According to the American Cancer Society, the mortality rates for liver, stomach, and kidney cancers in Native American people are twice as high as mortality rates for White people.[12] We request that the Committee support the Initiative by continuing to appropriate funds for the Initiative in FY25 and increasing funding to $10 million.

Request: Fund the Good Health and Wellness in Indian Country (GHWIC) program at $30 Million for FY25

The GHWIC program provides essential funding support to Tribes, Tribal organizations, and UIOs to improve chronic disease prevention efforts, expand physical activity, and reduce commercial tobacco use. The program is currently funded at $24 million, but additional funding is needed to maintain programmatic success and account for rising costs. NCUIH requests the Committee support the GHWIC program by increasing funding to $30 million for FY25.

Request: Protect Funding for HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment

American Indian and Alaska Native people have the highest rate of undiagnosed HIV cases compared to other racial/ethnic groups in the U.S.[13], and according to IHS, as many as 34% of the American Indian and Alaska Native people living with HIV infection do not know it.[14] UIOs are an important resource for urban American Indian and Alaska Native people for HIV/AIDS testing and referral to appropriate care Maintaining UIO programmatic support for HIV/AIDS is critical to safeguarding the health of urban American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Therefore, we request that the Committee protect funding for HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention programs, such as the Minority HIV/AIDS Fund, by maintaining funding for these programs at current levels.

Request: Reclassify Contract Support Costs and 105 (l) Tribal Lease Payments as Mandatory Appropriations

We are also in strong support of the TBFWG’s proposal to reclassify Contract Support Costs (CSC) and Section 105(l) Tribal Lease Payments as mandatory appropriations. These accounts are already mandatory in nature, and their inclusion in the discretionary budget makes it difficult for other programs to expand under discretionary funding caps. In 2014, the Appropriations Committees highlighted the challenging nature of these payments, stating, “Typically obligations of this name are addressed through mandatory spending, but in this case since they fall under discretionary spending, they have the potential to impact all other programs funded under the Interior and Environment Appropriations bill, including other equally important tribal programs.”[15] This proposal will make sure that other IHS programs are not impacted by these costs and can receive true increases to their line items. Reclassifying as mandatory appropriations will have no direct impact on the federal budget and does not conflict with restrictions set forth by the Fiscal Responsibility Act. On July 12, 2023, NCUIH joined the National Indian Health Board and 21 Tribal Nations and Native Partner Organizations in sending a letter to House and Senate leadership in support of this proposal.

Conclusion

The federal government must continue to work to fulfill its trust obligation to maintain and improve the health of American Indians and Alaska Natives. We urge Congress to take this obligation seriously and provide the I/T/U system with the resources necessary to protect the lives of the entirety of the American Indian and Alaska Native population, regardless of where they live. The requests outlined herein are an important step towards fulfilling this obligation, and we respectfully request your consideration of each request.

[1] Relocation, National Council for Urban Indian Health, 2018. 2018_0519_Relocation.pdf(Shared)- Adobe cloud storage

[2] Indian Health Service, IHS National Budget Formulation Data Reports for Urban Indian Organizations (2023), https://www.ihs.gov/sites/urban/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/IHS_National_Budget_Formulation_Reports_Calendar_Year_2021.pdf

[3] Elizabeth Arias, et. al., Provisional life expectancy estimates for 2021, Vital Statistics Rapid Release; no 23, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics System (Aug. 2022), available at DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:118999.

[4] U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans (Dec. 2018), available at: https://www.usccr.gov/files/pubs/2018/12-20-Broken-Promises.pdf; The National Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup, Advancing Health Equity Through the Federal Trust Responsibility: Full Mandatory Funding for the Indian Health Service and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships, The National Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup’s Recommendations on the Indian Health Service Fiscal Year 2024 Budget 17 (May 2022), available at: https://www.nihb.org/docs/09072022/FY%202024%20Tribal%20Budget%20Formulation%20Workgroup%20Recommendations.pdf.

[5] 25 U.S.C. § 1601(1)

[6] 25 USC § 1602.

[7] The National Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup, Honor Trust and Treaty Obligations: A Tribal Budget Request to Address the Tribal Health

Inequity Crisis, The National Tribal Budget Formulation Workgroup’s Recommendations on the Indian Health Service Fiscal Year 2025 Budget (April 2023), available at: https://www.nihb.org/resources/FY2025%20IHS%20National%20Tribal%20Budget%20Formulation%20Workgroup%20Requests.pdf.

[8] IHS FY25Congressional Justification, https://www.ihs.gov/sites/budgetformulation/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/FY-2025-IHS-CJ030824.pdf

[9] P.L. 118–31

[10] Contract Support Costs and Sequestration: Fiscal Crisis in Indian Country: Hearings before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs.(2013) (Testimony of The Honorable Yvette Roubideaux)

[11] H.R.2882 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, H.R.2882, 118th Cong. (2024), https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2882/text.

[12] Siegel RL , Giaquinto AN , Jemal A . Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024; 74(1): 12-49. doi:10.3322/caac.21820.

[13] IHS Awards New Cooperative Agreements for Ending the HIV and HCV Epidemics in Indian Country. (2022, September 27). Retrieved January 5, 2023, from https://www.ihs.gov/sites/newsroom/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/HIV-Funding-PressRelease09272022.pdf

[14] Indian Health Service, HIV/AIDS in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. Retrieved August 8, 2023, from: https://www.ihs.gov/hivaids/hivaian/#:~:text=The%20IHS%20National%20HIV%2FAIDS,Get%20tested%20for%20HIV.

[15] Explanatory statement, DIVISION G- DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, ENVIRONMENT, AND RELATED AGENCIES APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 2014. https://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20140113/113-HR3547-JSOM-G-I.pdf