The Importance of EHR Interoperability for Urban AIAN Veterans

In a recent ranking of the health care systems of high-income countries, the Commonwealth fund ranked the United States the worst out of the 11 analyzed. Along with the well-documented problems of high cost and poor access, the ranking also focused on the administrative inefficiencies in the American System. Unlike other countries, the United States has failed to implement a functioning system of portable Electronic Health Records (EHRs).i This failure leads to the “blocking” of crucial health information and the impairment of the “safety, quality, and effectiveness of care provided to patients.”ii The ability for patients to access their EHRs across multiple providers is important for better care coordination.

In an attempt to address this failure, in 2009 President Obama signed the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act to promote the adoption of EHRs by Medical Providers. Unfortunately, the HITECH Act did not provide adequate incentives to encourage the use of EHRs. By 2015, only 6% of physicians had the ability to share patient data across EHR systems.iii This failure effects the quality of care of every American, but the challenges are greatest for patients who must regularly interact with multiple disconnected healthcare providers, such as American Indians and Alaska Natives.

All federally-recognized American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs) are entitled to receive care through the Indian health system managed by the Indian Health Service (IHS). AIANs have historically served in the U.S. military at a higher rate than any other populationiv, and these veterans are also entitled to receive healthcare through the veterans’ healthcare system managed by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). However, AIAN veterans report significant challenges because IHS systems and VHA systems are not currently interoperable to connect and share patient information with each other.

The 144,844 AIAN Veterans who live in Urban Areasv face an even more complex challenge. Many cities with large populations of AIAN Veterans contain no IHS facilities. IHS-funded Urban Indian Organizations (UIOs) serve 39 cities. Still, UIOs do not provide inpatient healthcare services, so Urban AIAN Veterans must interact with local healthcare systems to fully meet healthcare needs, which do not currently speak to each other.

In the most recent American Community Survey Five-Year Dataset (ACS 2017-21), 9.4% of Urban AIAN Veterans (under age 65) report being “currently covered” by the “Indian Health Service” and 39.4% report being “enrolled for VA health care.” Interestingly, 4.5% report overlapping coverage from IHS and VA.vi

Table 1 lists the percentage of Urban AIAN covered by IHS and VA for the 20 cities with the largest Urban AIAN Veteran Populations from ACS. Unsurprisingly, IHS coverage is lowest in cities which contain no IHS facilities and no Urban Indian facilities (Washington-DC, Houston, Atlanta). The exception are Veterans in Denver and Dallas which report an approximately 5% IHS coverage rate even though those cities do not contain IHS facilities.vii It is possible that some veterans are categorizing their use of services by UIOs as “IHS Coverage” when responding to the American Community Survey. IHS is highest in cities with multiple IHS facilities (Phoenix, Oklahoma City).viii In general, in cities where IHS coverage is high, overlap with VA coverage is also high.

Table 1: IHS and VA Coverage in Twenty Metro Areas with Largest Urban AIAN Veteran Population.

| Metro Area |

% Covered by IHS |

% Covered by VA | % Covered by IHS and VA |

2021 Urban AIAN Veterans |

| Phoenix, AZ | 26.6 | 36.3 | 13.0 | 5015 |

| Los Angeles, CA | 1.6 | 38.4 | 0.4 | 4780 |

| New York, NY | 7.9 | 28.5 | 4.9 | 4149 |

| Washington, DC | 0.2 | 27.4 | 0.2 | 4033 |

| Seattle, WA | 6.2 | 38.5 | 5.1 | 3947 |

| Dallas, TX | 4.6 | 42.3 | 1.7 | 3843 |

| Houston, TX | 1.8 | 42.1 | 0.7 | 3633 |

| San Diego, CA | 7.6 | 50.2 | 3.8 | 2890 |

| Riverside, CA | 11.9 | 41.5 | 7.5 | 2738 |

| Chicago, IL | 2.9 | 39.2 | 1.1 | 2667 |

| Denver, CO | 5.4 | 37.5 | 1.9 | 2596 |

| Portland, OR | 7.5 | 33.6 | 2.5 | 2559 |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 42.3 | 37.8 | 22.4 | 2389 |

| San Antonio, TX | 2.8 | 53.0 | 0.8 | 2349 |

| Albuquerque, NM | 47.5 | 35.4 | 21.0 | 2097 |

| Atlanta, GA | 2.2 | 35.4 | 0.8 | 2059 |

| Las Vegas, NV | 6.6 | 38.7 | 3.2 | 2034 |

| Jacksonville, FL | 0.9 | 37.3 | 0.9 | 2022 |

| Austin, TX | 3.1 | 49.2 | 2.6 | 1895 |

| San Francisco, CA | 0.3 | 27.8 | 0.0 | 1873 |

There are multiple issues with interpreting these results. The ACA asks about IHS “coverage plans” in the context of a question about health insurance, so it is unclear how a respondent should answer if they receive some healthcare through IHS, but also some from other providers outside the IHS health system. It is also unclear if patients receiving care from IHS-funded Urban Indian Organizations would include themselves as part of “Indian Health Service” coverage.

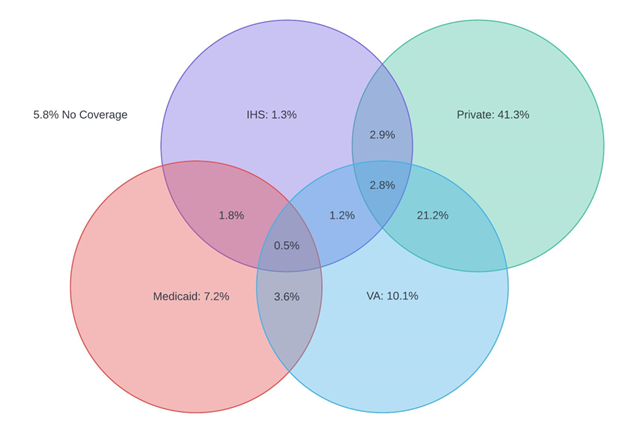

Adding another layer of complexity, Urban AIAN Veterans must also manage the overlap between the IHS and VA healthcare systems and their insurers (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Urban AIAN Veterans Overlapping Coverage

Only 1.3% of Urban AIAN Veterans receive coverage solely through IHS. Overlap with other healthcare systems and insurers is more common. 1.8% of Urban AIAN Veterans receive services from IHS while enrolled as a beneficiary of Medicaid. 1.2% of Urban AIAN Veterans receive services from both IHS and VA without any insurance coverage. 2.8% of Urban AIAN Veterans receive services from both IHS and VA while enrolled in private insurance. 10.1% of Urban AIAN Veterans receive coverage solely through IHS. 21.2% of Urban AIAN veterans receive services from the VA, while also enrolled in private health insurance.

The need for interoperability is clear, especially for Urban AIAN Veterans who may navigate multiple systems of care, that would benefit from coordination. In 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act passed and is currently being implemented with increasing requirements for interoperabilityix. In response to these requirements, IHS is piloting a “Four Directions Hubs” which connects IHS to the Joint Higher Information Exchange of the VA through the national Ehealth exchange as a positive reinforcement of the required effort. The pilot was implemented at 4 IHS sites with preliminary success. It is important that this effort can be scaled up to improve the multiple healthcare systems accessed by Urban AIAN Veterans to support the full I/T/U system.

i “Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly,” August 4, 2021. https://doi.org/10.26099/01dv-h208.

ii Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC). 2015. Report to Congress on Health Information Blocking. April 2015. Available at: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/reports/info_blocking_040915.pdf

iii Reisman, Miriam. “EHRs: The Challenge of Making Electronic Data Usable and Interoperable.” Pharmacy and Therapeutics 42, no. 9 (September 2017): 572–75. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5565131/.

iv Proclamation on National Native American Heritage Month, 86 C.F.R. § 60545 (2021), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/10/29/a-proclamation-on-national-native-american-heritage-month-2021/.

v U.S. Census Bureau, 2017-2021 American Community Survey 5-year Public Use Microdata Samples (2022), retrieved from https://usa.ipums.org/usa/sda/. Urban Veterans are defined as respondents who 1. Reside in a Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMA) which lies fully or partially within a Metropolitan Area with a population of 50,000 or more; 2. Were formerly in the armed forces or armed forces. CODEBOOK for Variable Descriptions: https://sda.usa.ipums.org/sdaweb/docs/us2019c/DOC/nes.htm

vi Ibid.

vii Locations. “Locations | Indian Health Service (IHS).” Accessed June 6, 2023. https://www.ihs.gov/locations/.

viii Ibid.

ix AAMC. “Electronic Health Records: What Will It Take to Make Them Work?” Accessed June 6, 2023. https://www.aamc.org/news/electronic-health-records-what-will-it-take-make-them-work.